Categories

Speciality Areas

Medical device flammability testing

For patient and carer safety, it is important that medical devices will not catch fire, or if they do they self-extinguish quickly. For years, pressure care cushions and mattresses had been required to be tested to furnishing flammability standards, in the absence of appropriate medical device flammability standards.

For cushions, specific medical device testing has been progressing well over the last decade or so with new flammability standards explicitly centred around wheelchair accessories, and this testing is now called up specifically in different parts of the world.

Can mattress testing follow suit?

In the absence of medical device flammability standards, procurement departments have been calling up furnishing standards in their stead for beds, cushions and mattresses. However, furnishing flammability standards vary around the world, and many of them have only subtle differences between them: there are International standards (such as ISO 8191-11 and -22), European standards (such as BS EN 1021-13 and -24), and National standards (such as BS 71775 in the UK). Most of these have two parts, one being a cigarette test and the other a flame test, and they tend to concentrate on two aspects – one being the tendency for the test item to catch light, and the other being how quickly they self-extinguish once alight. The subtle difference between standards can be just the times that either of these elements take to occur. There was an original version of ISO 7176-166, for testing the flammability of ‘upholstered’ items on a wheelchair, which was also just one of these iterations. (In the UK, on top of these, we also have more ‘aggressive’ heat sources, such as Crib 5 which used to be the norm for hospital mattresses, and Crib 7 for prison mattresses). One downside of the furnishing standards is that they stipulate that the heat source be placed at the junction of the seat and the back – a junction that does not occur with a single cushion or mattress on it own.

A standard cigarette

For a standard to be a good standard the test conditions need to be consistent and reproducible. A cigarette fails to meet these criteria. When the flammability standards were first conceived, the smokers’ norm was for untipped cigarettes, whereas these days most cigarettes are filter-tipped. The laws around cigarettes have changed over the years: in most countries they are now expected to have ingredients to inhibit their burning when left unattended. These are therefore different heat sources from those used in the original standards. The Crib heat sources are made from wood constructs, and they also are not necessarily reproducible heat sources.

So, what is a standard cigarette? In the early days of the development of the current cushion standards, it was found that there was considerable difference in heat output between each of the cigarettes from one packet, let alone between packets. In the USA there was an attempt to produce a ‘standard’ tobacco-based cigarette with a guaranteed consistent heat output, but this was not taken up, partly against a background of health risks around burning tobacco, and was not available internationally.

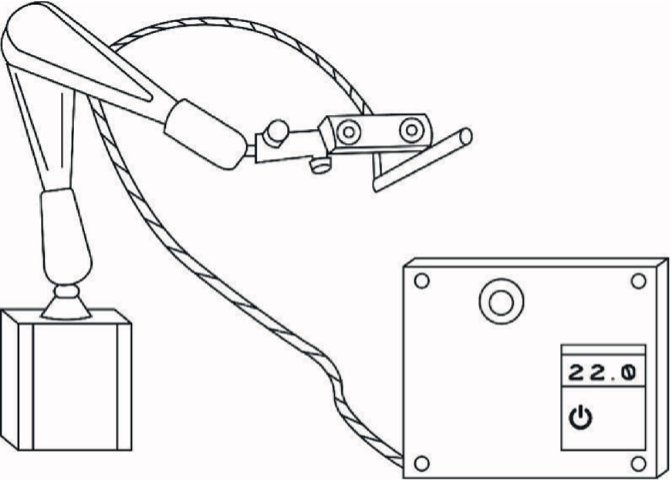

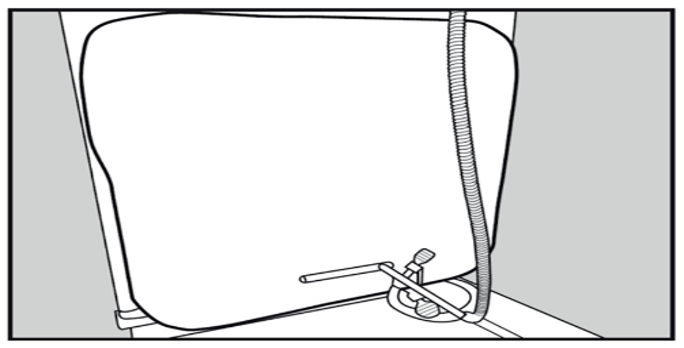

To address these challenges, a lab in Germany created a virtual standard cigarette. This was a cylinder in the shape of a cigarette which could be heated up to the temperatures measured in an ‘average’ cigarette of that time (Figures 1 and 2). This became the heat source employed in the first edition of a new flammability standard (ISO 16840-10:20147). This standard became the standard for use for just ‘non-integrated’ seat cushions and back supports. The use of a low heat source alone was selected for these items since the risk of injury to a wheelchair occupant from fire was very limited, whereas there was much more risk of tissue injury from inappropriate pressure care materials: it was felt therefore appropriate that restrictions on pressure care materials selection should not be prejudiced by fire retardancy properties being in the ascendancy. ISO 7176-16 continued8 as a butane flame test for testing the fire resistance of other wheelchair seating components – with the thinking being that these items might be more exposed to sources of fire than the items being protected by people sitting on them, and therefore being at greater risk of catching light.

The world moves on

Statistical analysis of flammability events affecting wheelchair users showed that most fires occurred as a result of electrical faults: protection in this area is covered by the requirements encompassed in ISO 7176-149. Further analysis showed that, otherwise, the risk of injury from fire was so low that the more aggressive flammability testing from the use of a flame test was an unneeded cost. In addition, with adaptation, ISO 16840-10 testing could be used to cover all postural support devices on a wheelchair, from cushions to positioning pads to arm supports, and this was covered in the revised 2021 edition10. At that time ISO 7176-16 was withdrawn.

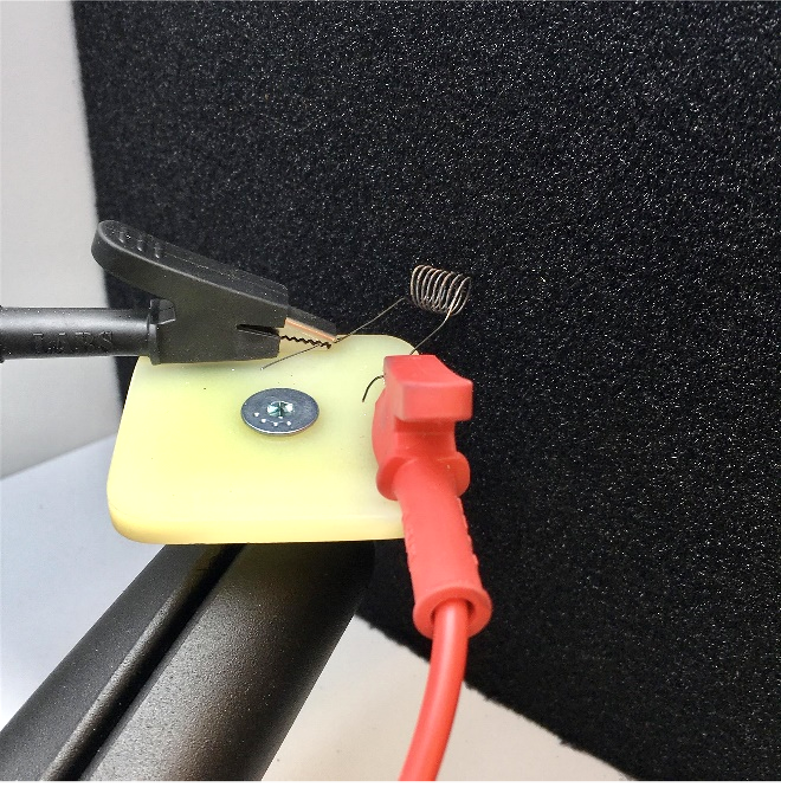

A new simplified, and less expensive, test method had been trialled and verified in different parts of the world, and full instructions for this have just become available as an updated set of Annexes as an amendment to ISO 16840-1011. This method involves a NiCr coil shaped to mimic the burn area of a cigarette (Figure 3).

Figure 3: NiCr coil in vertical test position

From a regulatory perspective, the use of flame retardants has come under scrutiny. In California, for example, the use of organohalogen flame retardants typically used to meet their TB 133 “present significant health risks to consumers, as established by overwhelming scientific research” and have now been banned. In the USA the FDA now specifies ISO 16840-10 for wheelchair cushion testing. In Europe, the two wheelchair standards EN 1218312 and EN 1218413 now call up ISO 16840-1010.

Mattress challenge

The challenges around testing bedding materials are more widespread than for wheelchair cushions and other seating-related devices. A wheelchair cushion will be used predominantly in a wheelchair, whereas a medical mattress may be used in a variety of environments, ranging from domestic, to care home, to hospital, to prison. The risks of fire in each of those different arenas vary significantly. In hospitals there is more constant vigilance at hand, and less risk from smoking materials, but there are other adverse agents such as oxygen or alcohol-based materials at hand. In some countries there is more dependence on sprinkler systems to ensure any fire is extinguished, rather than relying on the medical mattress to prevent the spread of fire. What the flammability tests do not provide for is the potential release of toxic materials as a result of burning, nor the relative inability of an ill person being able to move away from a burning environment.

One of the benefits of the new NiCr test method is that the current through the coil can be varied to match different heat outputs, and could be used to simulate the flame and the Crib tests, and be easily applied to the different surfaces of a mattress that might be at risk.

We are on the road to being able to offer an internationally acceptable medical device mattress flammability standard that matches the seating standard, and the opportunity to move away from furnishing standards for the bedding world. All thoughts and ideas at this stage would be most welcome.

References

- ISO 8191-1:1987 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture – Part 1: Ignition source: smouldering cigarette

- ISO 8191-2:1987 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture – Part 2: Ignition source: match flame equivalent

- BS EN 1021-1:1994 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture – Ignition source: smouldering cigarette

- BS EN 1021-2:1994 Furniture. Assessment of the ignitability of upholstered furniture – Ignition source: match flame equivalent

- BS 7177:2008 + A1:2 Specification for resistance to ignition of mattresses, mattress pads, divans and bed bases

- ISO 7176-16:1997 Wheelchairs – Part 16: Resistance to ignition of upholstered parts. Requirements and test methods

- ISO 16840-10:2014 Wheelchairs — Resistance to ignition of non-integrated seat and back support cushions. Requirements and test methods

- ISO 7176-16:2012 Wheelchairs – Part 16: resistance to ignition of postural support devices

- ISO 7176-14 Wheelchairs – Part 14: Power and control systems for electrically powered wheelchairs and scooters. Requirements and test methods

- ISO 16840-10:2021 Wheelchair seating – Part 10: Resistance to ignition of postural support devices. Requirements and test methods

- ISO 16840-10:2021/Amd1 2024 Wheelchair seating – Part 10: Resistance to ignition of postural support devices. Requirements and test methods AMENDMENT 1. Amended with additional Annexes

- EN 12183:2022 Manual Wheelchairs. Requirements and test methods

- EN 12184:2022 Electrically powered wheelchairs, scooters, and their chargers. Requirements and test methods