Categories

Speciality Areas

Design for Life Roadmap

The recently published DHSC Policy Paper “Design for Life Roadmap” concerns the building of a circular economy for medical technology, but are its timescales ambitious enough?

The 2024 Policy Paper from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) entitled “Design for Life Roadmap – Building a circular economy for medical technology”1 contains thirty ‘actions’ across six ‘problem statements’ to set out the fundamental challenges which the DHSC aims to address to develop and embed a circular system. By addressing these challenges, the programme will aim to deliver a circular system by 2045. 2045? Many medtech companies are already well down that path: it is the behemoth of the public sector which needs to change, and with a much greater sense of urgency!

The arguments for a circular economy are strong.

- The DHSC calculates that a functioning circular system will mean that more of the £10 billion the NHS spends on medical devices could be spent in the UK.

- By reducing reliance on volatile supply chains, and growing local capacity to meet demand, circularity will protect health systems from global supply shocks.

- Circular approaches to medtech will reduce waste and carbon emissions – the paper quotes, for example, that the NHS throws away 133,000 tonnes of plastic each year, which is roughly the same weight as all the household waste generated in Leicester, but the NHS only recovers a ninth as much of the plastic2.

- Circular devices are often more cost-effective than single-use. In several case studies, savings of more than 50% could be realised compared with conventional single-use equivalents.

Sense of urgency?

The roadmap’s thirty actions have been divided into how ‘mature’ they are, where indicatively high-maturity actions could be completed in 2024 to 2027, medium-maturity actions in 2027 to 2029, and low-maturity actions in 2029 to 2031. The outcome is that there’s only three actions under the high maturity heading, the reason being that the DHSC deems the others to require significant research activity before they can commence. The three actions to complete over the next three years are: bland statements to collaborate with other policy-making bodies, present a full ecosystem roadmap, and to have the circularity of medtech embedded in communications, engagements, and strategies.

The paper states that the most relevant problem for clinicians and patients is behavioural change, but the Action to develop a behavioural change plan is not until the 2029-2031 window. The paper spells out clearly that it is behavioural changes that will drive the rest.

Other Actions which are kicked down the road into the same time window include: “Develop a decontamination infrastructure framework” and “Establish a materials recovery and recycling framework”. These structures are already in place within local councils through their recycling pathways and their loan stores upon which the NHS could base these actions within a much shorter timescale.

Under the Commercial Incentivisation platform, the paper hits right at the core of the problem. Procurement is beset by short-term restrictions prescribed from above: short term budget restraints, short term cost savings, lower up- front costs rather than life-time value. While these drivers are in place, procurement behavioural changes will not occur. NHS Supply Chain agreements will continue to be based on what they have always done, and on how things are described, and not on outcomes – neither clinical nor lifetime cost benefits.

What do we offer already?

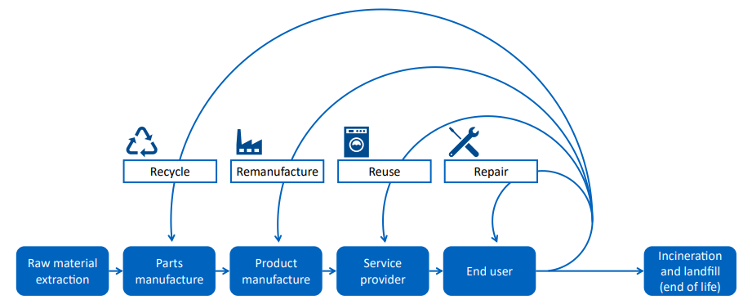

Much of the paper concentrates on the acute sector and what hospitals are doing with the procurement, use, and disposal of their instruments. Looking back over the forty years where I’ve been involved with both assistive products and with equipment decontamination I see many areas where those of us in the medtech section have already been offering solutions right across the board in the paper’s circular economy system (Figure 1). Let’s consider the four key activity headings.

Recycle

Looking at products that BES Healthcare offers, as an example, that can be recycled we have been selling washer- disinfection machines for nearly 30 years, and when the user decides to upgrade their model we have either refurbished the old machine for reuse by another site, or have stripped it down so that the stainless steel can be recycled.

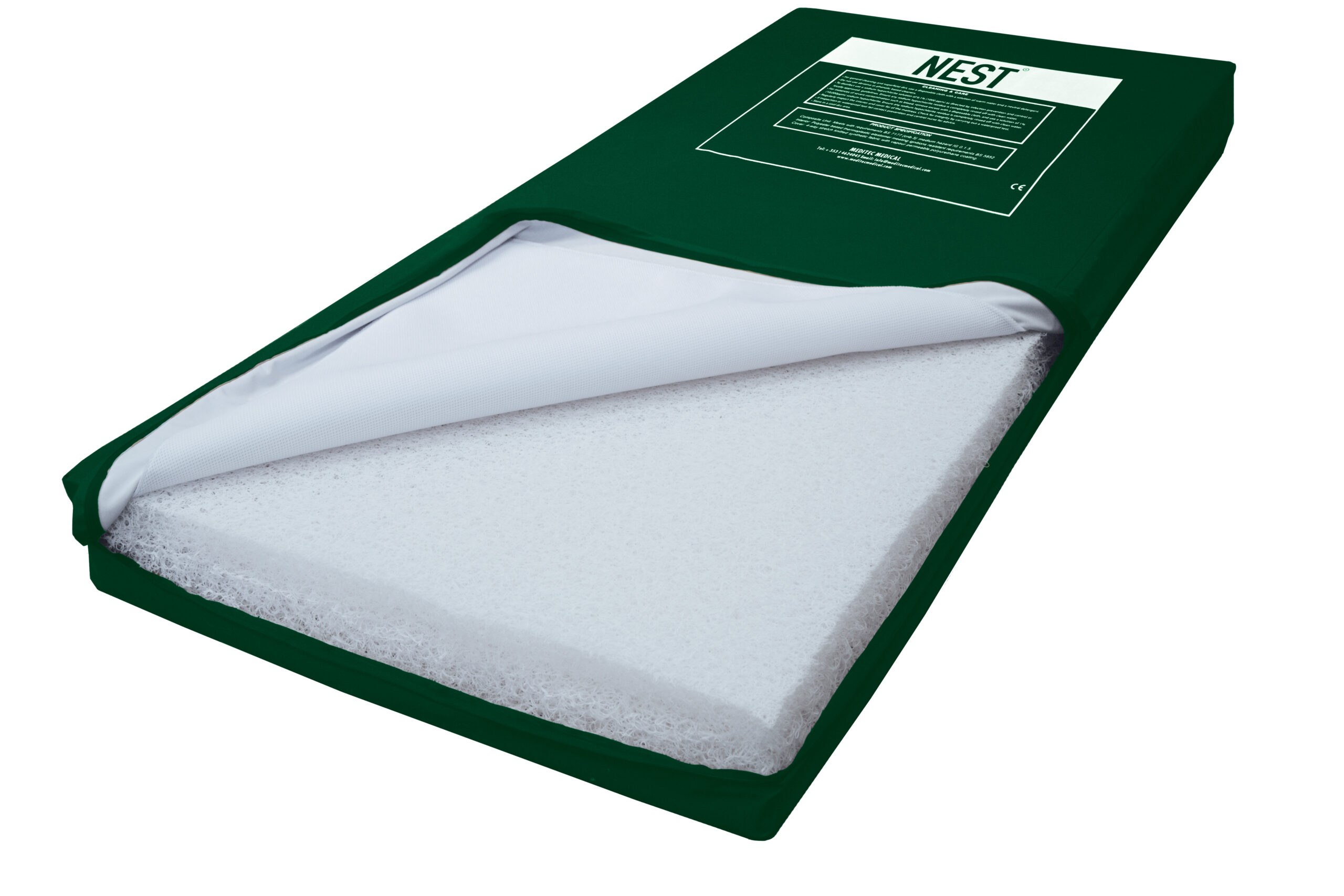

Excitingly, we have recently taken on the line of NEST mattresses and cushions (Figure 2)3 where, unlike most PU foam mattresses and cushions, the core material can be washed, disinfected, and reused for up to 8 years. Once its useful life has ended, it can be shredded into small pieces that can be recycled back into the original core plastic.

Figure 2. A NEST thermoplastic elastomer filled mattress

Many loan stores have skips being filled with metal items that have ended their useable life, ready to go off to the scrapyard to be recycled. The community side is already ahead of the game in many respects.

Remanufacture

Children’s equipment needs changing regularly as the child grows. Our industry has for many years been providing equipment that can be adjusted to meet these changing needs, and then later also be refurbished for re-use with another child.

About 35 years ago, John Prout identified that the original Scandinavian Tripp Trapp high chair could be modified to make it more adapted to, and safer for, youngsters with behavioural or mild physical challenges – which he incorporated into the Breezi range (Figure 3)4. The chair can be adjusted for the individual as they grow and their needs change. Thereafter, the modularity of the components and accessories have meant that an original chair can have items replaced or upgraded to meet the specific needs of the next user, without the need for a completely new item. As we have updated the designs of these elements we have worked to make sure that they are retrofittable to the original models.

Figure 3. A Breezi high chair with positioning aids

Repair and Reuse

Wheelchair services and loan stores have long been providing repair and reuse services, and so again the community side of the NHS and social services have led the way: this was streamlined in the 1990s with the creation of the Integrated Community Equipment Stores. It was these that fitted themselves out with automated washer- disinfectors for labour-efficient and reproducible cleaning and disinfection of the loan equipment, and at the same time protecting staff from the risk of infection from the aerosols created by hand-scrubbing or steam-cleaning the equipment.

The tightening of regulations and standards has moved forward the decontamination side of reuse. The MDR has made it explicit that CE marked medical devices can only be decontaminated by chemicals and equipment that are themselves designated as CE marked medical devices. New standards such as those in the BS EN ISO 15883 series5,6 provide the requirements which this equipment shall meet.

Figure 4. The K+F CE Class IIa bed and mattress washer-disinfector7

On the re-use front, having products that can be adjusted and modified as the user’s body shape or needs change or that can be adapted to another user, is a route already available in the primary care market. What is valuable here is that there’s a plethora of manufacturers of ‘after- market’ accessories that can be used to broaden and extend the use of the original products – items that have been designed and CE-marked for this purpose.

Usable life

One aspect that is not really tackled in depth in the paper is the usable life of a product – spending twice as much in the first place might source a product that lasts ten times as long! Examples from my personal experience go back over 30 years. Foam cushions have been in use for a very long time and are great pressure care products when new, but their shelf life is quite short, and the foam develops a ‘set’ quite quickly. Cascade Designs came along with the Varilite range of cushions8, using the technology from their popular

ThermaRest camping mattresses, and placed foam into an adjustable airtight bag that combined the envelopment provided by the trapped air with the stability of foam, but without the foam getting fully compressed, which extensively extended the life of the foam.

When we introduced the Bodypoint range of belts and harnesses, the first range to meet the ISO 16840-3 performance tests9, I received an apology from the clinical engineer at what was then Stanmore’s wheelchair service, that their ordering had decreased since the belts lasted the ‘lifetime’ guarantee, and then could still be reused on other chairs. Paying a little extra for quality on day 1, provides savings over a lifetime.

Another example is the Matrix seating system, now also available in the updated FreeForm seating system (Figure 5)10, which is made up of small adjustable components which allow for regular adjustment to meet a client’s changing needs for their life, and in a more compact and lightweight alternative to the likes of foam carved or moulded seating systems – and in a system that often can be built at the client’s first fitting. The components can later be re-used in other seating systems.

Figure 5. The FreeForm seating system

As another example, unlike foam cushions and mattresses that cannot be readily cleaned and disinfected if soiled, the NEST cushions and mattresses3 can be decontaminated as often as needed in a washing machine or washer- disinfector, extending their life considerably, and then tick the sustainability box at the end of life by being shredded and recycled.

Conclusion

Along the roadmap for a circular economy, the primary care sector is already well down the road, and the acute sector could make accelerated progress by learning from what is already on offer. The main obstacles that need to be addressed are the deep rooted behavioural ones around product specification and prescription, and the short-term drivers of our procurement processes. These issues need to be tackled right at the outset to give change a chance: adopting a pilot approach might be a useful way forward to reduce the perceived risk of transformation? However, how many pilots have we seen in the NHS where the Not Invented Here syndrome permeates the system? And why not be more ambitious and target this for 3 years’ time rather than 7 years?

References

- Design for Life roadmap (publishing.service.gov.uk)

- Calculated using Local authority collected waste management – annual results 2022/23, Local Authority Profile, Leicester City Council (2023), Waste Rates, Open Leicester

- https://www.beshealthcare.net/our-products/assistive- technology/nest-mattress/

- https://www.beshealthcare.net/our-products/assistive- technology/seating-systems/breezi-high-chair-range/

- ISO 15883-5:2021 Washer-disinfectors — Part 5: Performance requirements and test method criteria for demonstrating cleaning efficacy

- ISO DIS 15883-7:2024 Washer-disinfectors — Part 7: Requirements and tests for washer-disinfectors employing chemical disinfection for non-critical thermolabile medical devices and health care equipment

- https://www.beshealthcare.net/our-products/infection- prevention/equipment-washer/kluge-fielitz-equipment-washer-disinfector/

- https://www.beshealthcare.net/our-products/assistive- technology/wheelchair-cushions/varilite-evolution-wheelchair-cushion/

- ISO 16840-3:2022 Wheelchair seating — Part 3: Determination of static, impact, and repetitive load strengths for postural support devices

- https://www.beshealthcare.net/our-products/products/free-form-seating/